The ALIEN Series – Modern Hollywood’s Rise and Fall and Wondering Why the Fuck Ridley Scott Gets So Much Credit for ALIEN

Thanks for joining me for my first (and probably last, since I didn’t plan on this) segment of some random shit. If you’re sensible by even the lowest measures, you probably often wonder why Hollywood sucks so much ass these days. Well, the answer is out there, but it won’t specifically be here. Here there be a tracking of the Alien movies and its reflections on the modern Hollywood system, from the infant stages of the blockbuster to pretty much right now. I don’t pretend to be insightful. I just like talking shit.

This is an extremely long post. Basically I wanted to talk about the Alien series and its place in film history and ended up with this gigantic pile of shit. Having contracted writer’s block for just reviews, my cure was to write this abominably-long nothingness. Writing this was like a jigsaw puzzle of fun, so I apologize if the coherence is off in some places. Honestly, this was just an excuse to scour the internet for photos and look back on some old favorites and name-drop some of my favorite (sci-fi) flicks. Anyway, here’s some random shit:

With the anticipated Prometheus hitting North American theaters wide this week, I’ve decided to revisit the series. I’ve always considered myself to be a somewhat amateur film historian. Okay, maybe just an amateur and not much of a film historian. If there’s one thing I’ve learned watching movies and learning history, it’s that films are wholly of their time. Yes, they can be a critique on the prevailing attitudes of the day, but they’re often just as entrapped by them.

Today I want to revisit the Alien series and how it perfectly encapsulates and parallels the course of Hollywood from the birth of the blockbuster to, well, now; and why Ridley Scott’s fanboys need to stop kissing the man’s wrinkled old ass.

Everybody knows the film Alien, right? It’s that movie where a, well, alien, runs amok on a space-mining ship (mining spaceship?), killing off its crew one-by-one. Sounds like a shitty B-movie, doesn’t it? Yep, it’s pretty much forgotten now, except by pretty much everyone.

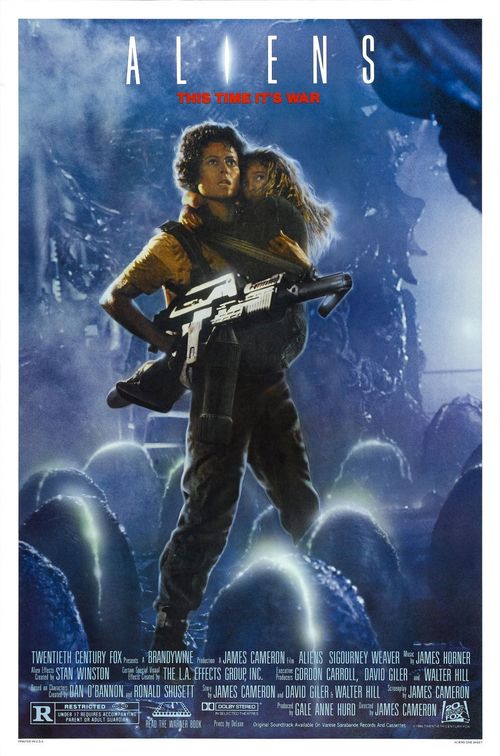

Everybody also knows the film Aliens, right? That totally different sequel by James Cameron, who went from doing stuff like The Terminator, The Abyss, and True Lies, to shockingly-bad and clichéd shitfests like Titanic and Avatar. Sure, your camera’s fancy and I think it’s cool you’re literally funding some kind of space-mining expedition and that you got to go down to the Challenger Deep, making me feel like shit because I know I’ll never get to do it. But good fucking god, can you stop ruining filmmaking for, you know, everybody? Your films make me feel like shit because they’re shit.

Uh, anyway, back to Aliens. Classic 1980s science fiction action film that is said to rival and/or surpass the original film by people who don’t know what the hell they’re talking about. It’s still an amazing film though. I think James Cameron really has a knack for the sequels. Sure, neither Aliens nor the overrated Terminator 2 surpass the originals, but when has he ever failed to deliver with an awesome sequel?

What do Alien and Aliens do that Alien 3, Resurrection, and the rest of them don’t? And, yes, it is a joke. Seriously, aside from the first two entries, the whole series is a fucking joke, and nobody’s laughing.

What’s even more shocking is the realization I came to awhile back: the Alien series perfectly parallels the rise of the modern Hollywood sensibility and its inevitable and satisfying fall.

In the mid-1970s to early-1980s, that thing we now revere as New Hollywood ended up collapsing on its own excesses, being replaced by a new New Hollywood: the blockbuster. In this period, Hollywood realized what all of the B-movie kings (like Roger Corman) were doing and decided to steal the method. For a number of years, director-driven projects and collaborative efforts existed rather side-by-side. In 1980, that all changed with the release of Heaven’s Gate.

The film has long been considered the gun that shot New Hollywood to death, and Cimino the shooter. Heaven’s Gate has been credited with changing a lot of things, including reversion of control back to studios and the death of director-driven excess. Cimino’s vision and demands drove up the budget astronomically. The release was an unmitigated disaster. Coppola’s One from the Heart in 1982 would follow suit. I guess if Cimino was the shooter, Coppola was the guy that buried it.

To be fair, Alien would have been made anyway. The favoritism towards high-concept films by major studios also happened at least five years before and, in hindsight, it seems as if the death of New Hollywood was a long time coming. Jaws was credited as the first of its kind, the blockbuster to revolutionize filmmaking. Other well-recognized and highly-acclaimed films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the original Star Wars trilogy, and Raiders of the Lost Ark would follow. Nearly all of these films were highly-collaborative, featuring input from everybody down the line. The results were impressive.

Above: Harrison Ford, cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, and Steven Spielberg during filming of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Caught between a New Hollywood on the verge of collapse and the rising revolution of high-concept filmmaking, it was in this cinematic (and perhaps also sociopolitical) climate that Alien was unleashed onto the world. After the monster success of Star Wars, Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett probably realized that Alien would become a reality. An idea like an alien running rampant on a ship and killing off the crew would have been relegated to the B-movies before such successes. In fact, before their script got passed onto the likes of Walter Hill, they were close to signing a deal with Corman, himself.

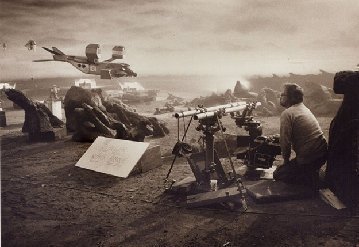

Above: on the set of Jaws.

O’Bannon and Shusett would present their initial script to studios as “Jaws in space”.

Results would be radically different.

So the system took a chance. Dan and Ron’s pitch: “Jaws in space”. O’Bannon’s well-known work prior to Alien included Dark Star, some effects work on Star Wars, and pretty much nothing else, although he had been attached to Jodorowsky’s Dune at one point. Shusett was a virtual unknown, his only credited work prior being W, in 1974. O’Bannon and Shusett would end up collaborating many times, including co-writing Dead & Buried (1981) and Total Recall (1990). Alien was their baby.

This is why everyone should stop riding Ridley Scott’s nutsack over Alien. Alien was a highly-collaborative process. Let’s face it, Ridley Scott’s movies suck ass, especially after 1982’s Blade Runner. None of the rest of his films could ever compare to his sci-fi duumvirate (yes, I’ve been waiting a long time to use that word) of Alien and Blade Runner. Does it not seem weird to anyone else that anything and everything else he does seems to pale in comparison to the duumvirs? Both films were the result of highly-talented and extremely creative individuals working as a team.

Now, for over thirty years, fanboys, fangirls and just plain fans, critics, average moviegoers, etc. have been showering Scott with so much semen praise. I have to wonder how many Alien fans actually realize that the film they love crediting Scott too much with was actually a highly-collaborative process. O’Bannon’s tenure on Dark Star was the initial spark. The rest of it would come in spades.

Above: the “alien” beach ball from Dark Star.

His experience working on this film would inspire O’Bannon to really want to make “an alien that looked real”.

The most surprising thing about Alien is its originality, and something that Hollywood of today should take note of highly. When asked where the ideas came from, Dan O’Bannon famously remarked: “I didn’t steal Alien from anybody. I stole it from everybody!” Hum… that sounds like today’s Hollywood. The Thing from Another World, Forbidden Planet, Bava’s Planet of the Vampires were just a few sources that served as inspiration.

Above: Planet of the Vampires, in which the protagonists discover a giant alien skeleton. That almost sounds familiar.

The difference between the Hollywood and filmmakers of then and now is that O’Bannon and the rest of the creative team did not just take ideas and craft them into a whole different animal; they also inputted their own creative ideas and thoughts into it. Hollywood shouldn’t stop stealing ideas; they should stop making shit from them. Back then they could make something of the ideas they had. Here, they managed to turn out one of the most original films of all-time, and it was stolen from everybody.

This film not only had two of the great sci-fi writers behind it, it also had a team that seemed to be assembled by God, himself, to create his vision. For instance, you had future great Walter Hill. Hill, David Giler, and Gordon Carroll headed production company Brandywine, with connections with 20th Century Fox.

Above: Southern Comfort (1981).

I love Alien. It’s one of my favorite films. But watching classics like Southern Comfort and even failed shitfests like Supernova make me wonder how the film would have turned out under Walter Hill’s direction. Of course, you have to wonder just how much control he had as producer, already.

Who to direct? Well, the initial choice was Walter Hill, now-famous for his action flicks like 48 Hrs. and the Warriors and Southern Comfort. Hill turned the job down, though he’d end up doing uncredited rewrites and producing. Hill and Giler’s rewrites would cause problems between them and O’Bannon and Shusett, who thought their rewrites were not making the script any better. Nevertheless, credit must be given to Hill and his comrades who not only saw merit in the project, but personally backed it.

They eventually ended up picking Ridley Scott to direct. Scott’s storyboards (which included designs for the spaceship) impressed 20th Century Fox enough to double the budget. Scott can be a good director. And he can be a fucking great director with the right creative team backing him up. Scott has a great eye for how things ought to look. But Scott wasn’t the only one with an artistic bent:

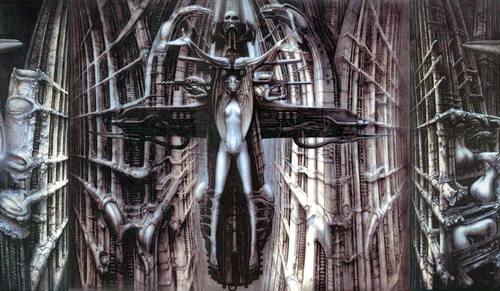

They had concept artists Ron Cobb (Dark Star) and Chris Foss (Dune) to work on human aspects of the film, like spaceships and suits. They also got the artist of Satan’s dreams and nightmares, H.R. Giger, for the alien design. Giger’s work is nothing short of brilliant. The biomechanicality of his work, its eroticism, and its ability to be both terrifying and beautiful at the same time still gives me the chills.

Giger’s work on the project not only served as the basis of the creatures, but eventually led to the filmmakers adopting a wholly unique approach to how the alien creature would get aboard the spaceship…

Dan O’Bannon described it as “oral invasion” and a metaphor for, well, basically the whole fear of penetration thing. Did I mention he described it as “oral invasion”? Alien was a movie whose creatures and concepts and designs often stood for symbolisms of male and female sexual imagery. From the design of the creature to images of oral rape and alien miscegenation and the male giving birth to the alien, Alien was only one notch below pornography in terms of subtlety (and that’s not necessarily a bad thing).

This was what set the film apart from so many. How do we get a creature on board? How about we impregnate one of the male crewmembers? The sexual imagery of Alien is one of the concepts that haven’t been used much since the first film. It’s just one of the aspects that made Alien unique and one that many “inspired” films (IE rip-offs) would continue to use and exploit (Inseminoid and Galaxy of Terror come to mind).

Above: Taaffe O’Connell being raped to death by a giant worm in Galaxy of Terror (1981).

Inspired by Alien and Japanese hentai, Roger Corman sets out to one-up his predecessors and make lots of money enticing horror fans who secretly wish they could worm-rape a hot woman to death.

Er, anyway, among others on the Alien creative team included: Roger Christian as art director (who went on to shockingly make shit like Battlefield Earth); Carlo Rambaldi who manufactured the alien’s head (and also worked on E.T., Deep Red, etc.); Brian Johnson as visual effects supervisor (who went on to work on The Empire Strikes Back); Martin Bower as supervising modelmaker; etc.

The cast, some of the finest actors of that and any other generation, were assembled to be as realistic as possible, described as “truckers in space”. I don’t think it would be fair to single out individual performances because, like the creative team behind the camera, each person in front of the camera did a terrific job as individuals in a team.

Some of Alien’s cast and Nostromo’s crew.

(Left to right: Yaphet Kotto as Parker; Sigourney Weaver as Ripley; Ian Holm as Ash)

The principal cast of Alien.

Left to right: Ian Holm, Harry Dean Stanton, Sigourney Weaver, Yaphet Kotto, Tom Skerritt, Veronica Cartright, John Hurt.

Long story short, Alien was the outcome of the creative input and output of the talents of many individuals, and not just Ridley Scott (who did do a fantastic job of directing)…

The result was a box office hit, a critical success, the birth of a classic, the creation of one of the most terrifying fictional creatures, the start of several careers and a franchise.

Jaws and Star Wars get a lot of credit for changing the game. I’d argue that Alien belongs right up there with them. Like so many of the highly-collaborative projects from this period, it ended up being a monster success and a bona fide classic. Alien is another example of a classic film from this period that set trends but also reflected the prevailing wind in cinema. Things looked quite good in Hollywood.

Alright, enough about Alien. If you want to read about the making of Alien, the Wikipedia page actually has a surprising amount of information, with sources that link to books about the making of the classic. Also try the documentary: The Beast Within: The Making of ‘Alien’ (2003). My point was basically that: (a) Ridley Scott is not a sci-fi god; (b) Alien is a product of its time and of the work of a team of highly-talented and creative individuals.

It would be at least seven years until a sequel was released.

By the time the mid-80s rolled around, the Reagan era was in full-swing and Hollywood kept on chugging. Studios took chances, creative teams kept on giving, and audiences everywhere kept rejoicing. Both independents and major studios thrived. Science fiction and action had become extremely popular genres in the wake of the birth of the blockbuster.

Above: Kurt Russell and Harry Dean Stanton in Escape from New York (1981).

Legendary horror and sci-fi maestro, John Carpenter’s now highly-regarded classic is an example of an independent sci-fi action film that was creative, inventive, a box office hit and a critical success.

A sort of crude example of this: James Cameron, a “graduate” of the “Corman School”, who had done work as art director on Battle Beyond the Stars and production designer on Galaxy of Terror and special effects work on Escape from New York. His first directorial job was Piranha II: The Spawning. His major breakthrough would be The Terminator in ’84; a box office success and now considered a sci-fi and action classic.

Cameron would be the one to get the sequel for Alien rolling. With B-movie sensibility still fresh in his mind, and lessons from working with Corman under his belt, Cameron sought to create a worthy successor to Alien.

First off, Cameron at this stage of his life was still with partner Gale Ann Hurd. Hurd, herself, had worked for Roger Corman, as executive assistant while at New World Pictures and soon became involved in production. While with Hurd, Cameron created, arguably, his four best films: The Terminator, Terminator 2, The Abyss, and Aliens.

Cameron, who was a fan of the first Alien, opted for a different approach: more terror, less horror. My feeling was that if they decided to create a straight-up horror sequel, they probably thought it would end up feeling like a rehash of the original, rather than something fresh. That’s just my take, anyway.

Cameron wrote ninety pages for Aliens while filming the Terminator and was ultimately given approval by 20th Century Fox after the latter became a hit. Weaver would return to the role of Ripley after a meeting with Cameron. Aliens would ultimately draw inspiration from the Vietnam War and would tackle issues like military-corporate interests and bureaucratic ineptitude that would be re-explored in The Abyss and Avatar.

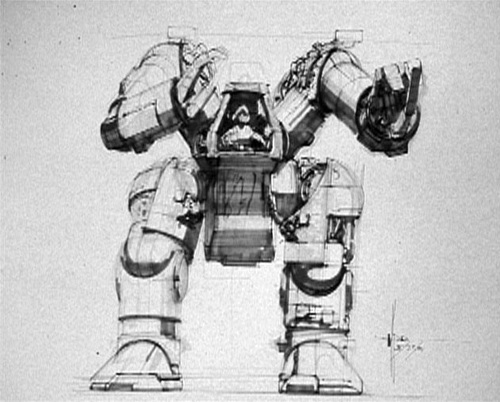

Alongside the duo, Walter Hill and his friends at Brandywine would produce. Cameron has always had a flair for the theatrics part, and his eye for visuals is no less important for Aliens. But once again, a killer creative team was brought on for the sequel. They managed to get Syd Mead, described as a “visual futurist” for work as concept artist and designer who also participated on Blade Runner and Tron.

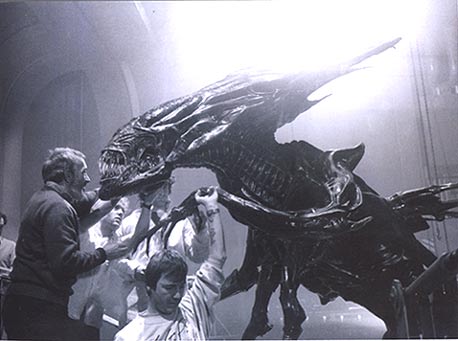

The brothers Robert and Dennis Skotak were brought on as visual effects supervisors. Both would go onto do other big-name projects, like Terminator 2 and Batman Returns, Robert most often for visual effects, and Dennis for visual effects or director of photography. And who could forget legendary Stan Winston and the alien queen?

The cast was a ragtag group, but once again it was comprised of able actors, who brought the film to life in front of the camera as well as the creative side did behind it. Despite initial problems and tensions on set between the producing team and the crew, everybody pulled through, and Aliens became a hit. It is now regarded equally alongside its predecessor; and just as Alien has a reputation for being a sci-fi horror classic, Aliens holds equal stature as a sci-fi action classic.

Aliens was wholly of its time and space in the mid-1980s. It was an era characterized by derivatives of former works, but also of immense creativity (whether they failed or not), as independents and majors competed on equal footing. When sci-fi from this period was good, it was fucking good. Examples of highly-creative works from this period include: Blade Runner (1982), The Thing (1982), Videodrome (1983), The Terminator (1984), Back to the Future (1985), The Fly (1986), RoboCop (1987). Other examples of major studios backing creative projects include: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Gremlins (1984), and Ghostbusters (1984). Action films would also dominate, with stars like Schwarzenegger, Stallone, Willis, Van Damme, Norris, and Seagal becoming household names. It’s not surprising Aliens was made in this period.

I honestly cannot get over the amount of sci-fi works from this period that are impressive, creative, watchable, and, above all, fun. This article is really about the major studios, but even independents and non-Hollywood filmmakers were releasing ambitious, if flawed, works. From works that were shameless rip-offs, to films that were hindered by budget limitations, to major studio productions and foreign films, it makes me sad that we can’t have what they had, today.

Above: still from Critters (1986).

Even the independents were churning out films with flair. Wrongfully accused of being a Gremlins rip-off, Critters was an example of ‘80s sci-fi goodness.

Above: still from Lifeforce (1985).

The (in)famous and (in)comparable Cannon Group’s attempt at sci-fi greatness.

Did I mention that Dan O’Bannon wrote this flawed wonder, too?

Above: Akira (1988).

It might have a weak ending, but this adaptation of the over-2000 page manga of the same name is a seminal anime and a Japanese cyberpunk classic.

The Alien series thus far had two films that were titans of sci-fi, a sequel that actually lived up to its predecessor… Could the streak continue? In a word: no.

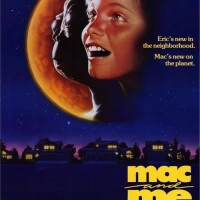

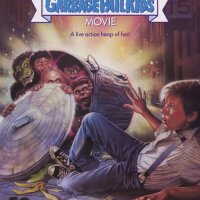

The late 1980s came along. Unfortunately for us, the late-80s presented as many opportunities for watchable films as it did crap. Garbage sequels like Ghostbusters II and rip-offs like Mac and Me and Leviathan exemplified the Hollywood tradition here. Again, don’t misunderstand me. I like a lot of films from this period, but it’s clear that the route was only downhill for Hollywood. As an example, of all of the underwater-related films released in 1989 (that was not The Abyss), Leviathan was the best one, DeepStar Six followed, and the rest were pretty much misses.

Above: still from Leviathan (1989). Late-80s, the tide of sci-fi begins to change.

One of about half a dozen films “inspired” by James Cameron’s The Abyss, Leviathan also took its cues from Alien and The Thing. Unfairly ridiculed, Leviathan was actually shot pretty well, had decent set designs and cinematography, a cast that included Peter Weller, Ernie Hudson, Richard Crenna and Amanda Pays, and a monster. What more could you ask for?

This is the period in which Alien 3 was born.

And like any botched birth, Alien 3 was unplanned, unwanted, premature, badly handled, feet-first and uncared for by the people that birthed it.

The 1990s rolled around. Reagan and Bush eras both gave way to the MTV President, Slick Willie, Bill Clinton. Hollywood pushed on. Blockbusters and high-concept films had become the norm at this point. I’d argue that the modern Modern period was truly borne out of Terminator 2, a film with a then unheard of budget of about $100 million, and directed by some egomaniacal jerk named James Cameron.

But while major studios continued to roll out sci-fi pics year after year, in hindsight it was becoming apparent that there was an increasing decline in terms of quality of the output beginning in the late-1980s. This was also true of horror films. Horror had become dominated by cycles of slasher films throughout the 1980s, and in the early 1990s was virtually dead, with few notable exceptions (Candyman comes to mind). Independent studios fared even worse. These weren’t the only problems, there were some far bigger and far more lasting…

Above: Demolition Man (1993) with Sylvester Stallone and Wesley Snipes.

An example of a mid-90s sci-fi actioner that didn’t completely suck ass.

Sidenote: this is such an awesome shot. Great cinematography.

Unfortunately, the 1990s presented a series of problems for filmmakers (which had been festering since the late-80s). Studio control and decision-making was one. Lack of creativity was another. Alien 3 would ultimately be a failure due to lack of creativity, but more because of changing attitudes in Hollywood, mostly towards the dumb and the useless. The early ‘90s was a period of time when a lot of independents faltered, were pushed out of the business or were swallowed up by the majors. The 1990s, where Alien 3 and Alien: Resurrection found themselves, was a period which let this

come to pass.

The problem isn’t the film itself (though you could certainly make the argument). The problem is the decision-making involved which led to its production and the downfall of its producers.

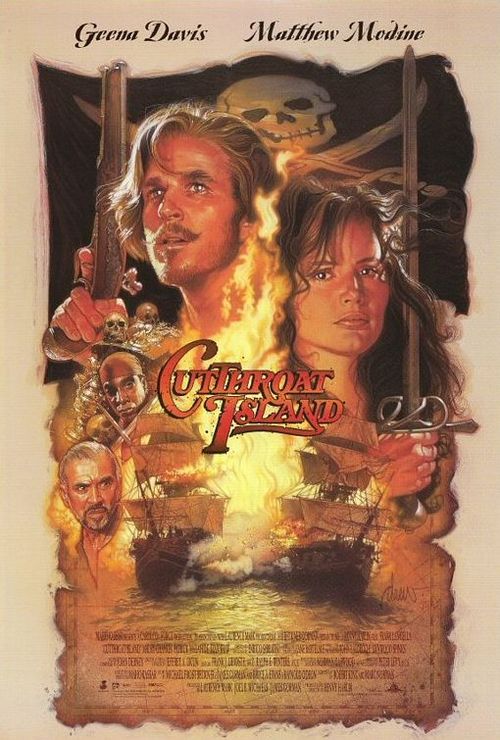

Unbelievably (or believably, depending on your point-of-view) the story goes that they passed on the Verhoeven/Schwarzenegger orgiastic bloody violent fucking epic Crusade to produce that bomb. Proof that Hollywood had no idea what it was doing and that dumbass executives in charge could never be a good thing.

Cutthroat Island was such a huge bomb that it bankrupted Carolco Pictures. Carolco was an independent studio which hitherto had managed to stay in the game with box office successes such as Total Recall, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Universal Soldier, Basic Instinct and Cliffhanger. So you have to wonder what the fuck they were thinking betting their entire company on this and Showgirls? Maybe that’s why they didn’t give Verhoeven the money because he already had it to make Showgirls.

But this was not really an isolated incident of stupidity and shortsightedness. In fact, this period would give way to some major disturbing trends that we still see today. For instance, Hollywood at this time began the tradition of hiring and firing multiple screenwriters and generally fucking up everything to do with production. As an example of this, for Alien 3, they got the renowned sci-fi writer and heartthrob William Gibson, who penned the cyberpunk classic Neuromancer, to turn in a screenplay.

Above: depiction of Chiba, from Neuromancer (artwork by Andrew Porter, aka PHATandy).

If you’re watching a film, specifically Alien 3, and it feels like it was written by a dozen different people and directed by about half that, don’t despair. Alien 3 was a film that exemplifies the typical studio fuck-up of a hectic and shoddy production, bad decision-making, bureaucratic incompetence, trademarks of Hollywood that continue now, into the present era (look at G.I. Joe: Retaliation as one of the latest examples).

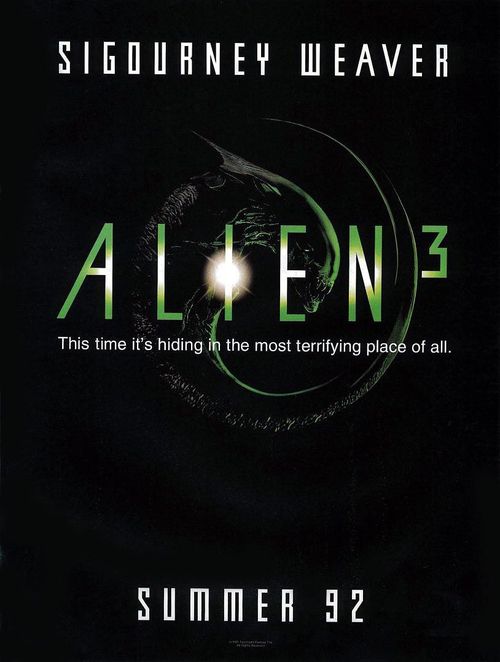

The anticipation for Alien 3 was probably running pretty high. There was even a teaser trailer that suggested that the aliens would come to motherfucking Earth. You went from a lone alien on a ship, to a myriad on a terraforming colony, and now you want a shitload on Earth? Fuck yeah, when can I see this?!

Answer: never.

William Gibson was only the first in a long line of writers hired and fired for this project. While Sigourney Weaver continued to stress the fact that she was never going to play Ripley again (except for lots of money), Gibson decided to focus the story on Hicks and Bishop. Gibson’s story involved “airborne virulent contagion” and the development of alien warriors by Weyland-Yutani. According to Gibson, the version of his script floating around on the internet is “about thirty pages shorter” than the version he submitted and “became the first of some thirty drafts” by “many screenwriters” of which “none of [his] was used”. How completely fucked do you have to be to hire William Gibson and then promptly fire him and not even consult whatever little he actually came up with?

Above: behind-the-scenes during filming of Aliens. Left to right: Lance Henriksen (Bishop); Michael Biehn (Hicks); Carrie Henn (Newt); Bill Paxton (Hudson).

Gibson’s story would focus on Henriksen’s and Biehn’s characters.

Who were these other screenwriters? A bunch of nobodies, probably, right? Among them were:

Eric Red, who I was disappointed to find out wasn’t actually a Viking or Viking-related. He did, however, write two of my favorites, The Hitcher and Near Dark. Red’s story would kill off everyone who survived Aliens and take place in some kind of space bio-dome small-town USA. Red’s script reused Gibson’s virus idea, except this time anything and everything could be infected, which turned the space station into an alien. Yeah, you heard that right. It also featured cool shit like alien hordes facing off in a huge battle against the townsfolk and less cool shit like the alien-human hybrid (that was reused in A:R). Renny Harlin, the director, walked out after being shown this script, and Eric was promptly fired.

Next up was David Twohy, who would go onto to do shit like The Fugitive, The Arrival, Pitch Black and Below. Twohy’s version would feature a prison planet (a concept which would be used in the final script, but also in Twohy’s own The Chronicles of Riddick). His vision was that this prison planet was being used for illegal experiments, carried out on unsuspecting inmates who were mock-executed via gas chamber. The experiments would involve the alien creatures, of course. Also featured were failed alien clones, people getting sucked through hulls, and different types of aliens (concepts which were all recycled for Alien: Resurrection). Unfortunately, the new director, Vincent Ward, didn’t want to work with Twohy, so he and his draft were scrapped.

Three strikeouts should be enough, right? Well, remind yourself never to play baseball with Hollywood execs. Vincent Ward (a critically-acclaimed New Zealand director), himself, and his co-writer John Fasano began crafting an entirely new story, where Ripley’s escape pod would crash into a “monastery-like satellite”, filled with “Luddite-like monks”. The story would have involved the monks having to deal with the presence of a woman, the increasing reality of the presence of the alien creature, and Ripley’s own soul-searching. It would have had all of the religious symbolism and allegory, visual wonder, and alien mayhem. You know what? This actually sounds pretty fucking original.

But no, they got booted off, too. Why? I honestly have no idea. I guess they were running low on time. Instead, Walter Hill and David Giler took control of the screenplay. They melded elements of the Ward and Fasano script with some of Twohy’s concepts (notably the prison planet). But that wasn’t the last of it. The screenplay would be reworked again by the director and author Rex Pickett though Pickett’s work would ultimately be rejected.

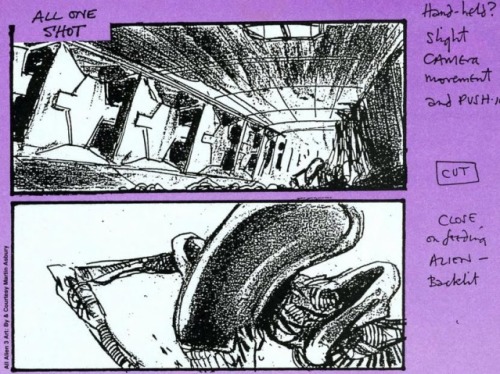

Wait, who was directing this abomination again? None other than then-unknown David Fincher. Fincher, unsurprisingly, would complain later that the studios weren’t giving him enough creative freedom. You know what’s really funny? After the colossal amount of rewrites, they began filming this turd, already having spent $7 million, and without a finished script. Good fucking god.

Above: Fincher’s classic, Seven (1995).

Like directors Scott and Cameron before him, David Fincher had an eye for visuals. Unfortunately, the studios effectively fucking blinded him for Alien 3.

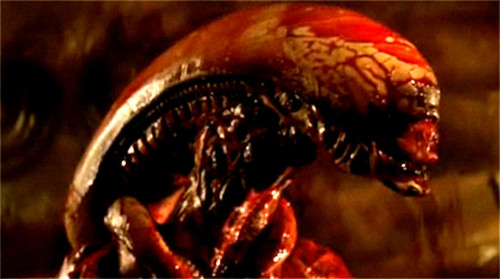

You’d think that’d be enough to convince you. Here’s more bad news. Stan Winston, unsurprisingly, did not return to work on the visual effects for Alien 3. Instead, he referred the filmmakers to two former workers of his studio: Tom Woodruff, Jr. and Alec Gills. Now I’m not saying they did a bad job, but… Wait, I guess I am… After budget cutbacks, continuous rewrites, and studio shenanigans, the alien hordes were reduced… to this:

Oh, and say hello to bluescreen effects:

It’s a pity. You had plenty of creative people working on this film, or attached to it at some point, and I just don’t mean the writers and director. Mike Worrall and Stephen Ellis produced concept art for Vincent Ward’s aborted version. Ward, himself, had quite the visual eye. John Eaves, notable for his work on the Star Trek series, was a model maker. Whether or not they were more creative than the previous teams is not up to my judgment. The biggest difference was that on Alien and Aliens, everybody was working synchronously and harmoniously. This, however, was not a collaborative effort. On Alien 3 (and A:R, also) you had producer fuck-uppery, studio interference, constant script rewrites, directors being replaced, that the creative force behind the work suffered. All of that artistic merit means nothing when the film itself is a clusterfucked production.

So congratulations, guys, and I’m talking to you Walter Hill and David Giler and other Hollywood executives. You took the creative talents of about a dozen individuals (and that’s not including the writers and director) and beat them to death with a shovel. There was a reason why Alien 3 felt like a hodgepodge of ideas, a forced product that reeked of studio control. I’m still amazed at how much a clusterfuck this production was but, at the same time, I’m not actually shocked by it. Why should I, when the prevailing wind in Hollywood was being blown out of its collective ass? It’s pretty easy to see the path we came down now…

But it’s not over yet… There’s still more… The 1990s was a period which tried to be creative but the works ended up feeling flat, uneven, boring and, quite frankly, callbacks to previous films did not seem subtle at all. Alien was pitched originally as “Jaws in space”. When you watch the film, Jaws does not pervasively enter your mind. I never once thought while watching Alien: “Man, this is like a rip-off of Jaws.”

The ’90s had films that did just as much stealing as did other films, but they clearly had you thinking it was ripped-off of something else. An example of this would be Under Siege. Don’t get me wrong, I love the film. I think I’ve pretty much established that I love eating shit with my shit-eating grin. But it clearly is and feels like Die Hard on a god damn ship. Not that I have a real problem with that, the world needs more Die Hard and Erika Eleniak’s tits. But I can be objective… Those are some really nice boobs… I mean, seriously, it’s pretty much a rip-off with no actual or real creativity. Fucking fun, but it nonetheless exemplifies the Hollywood mentality. Go where the money can be found.

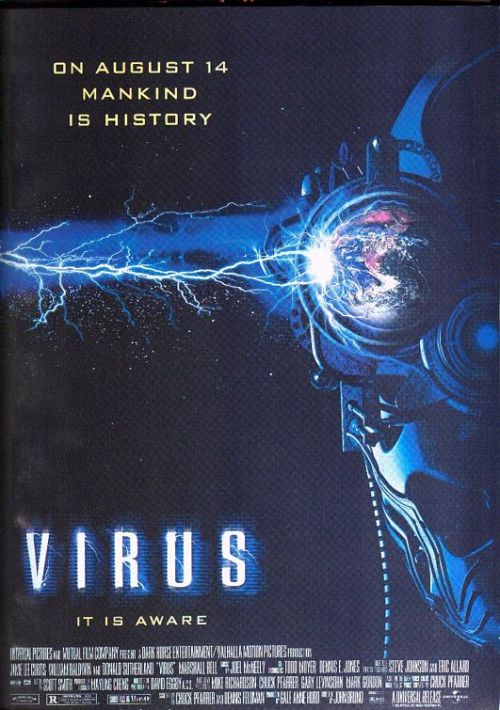

Not all films were like this, but many did feel tired, old and clichéd. And this became worse as the decade wore on. Who could forget Waterworld? But, ultimately, I think it was films like The Postman, Virus, The Phantom Menace and Alien: Resurrection, itself, that eventually led to a dearth in Hollywood’s creativity. The Matrix should have kept the trend of creativity going, but something happened along the way that fucked it all up. Oh yeah, sequels.

Sidetrack, but still relevant: long story short, Virus was one of the last real big chances Hollywood took and an unfair way to cap the end of the 20th century. It’s actually mindboggling that a major studio would chance a film like this. Regarded as a terrible film by most people’s accounts, I, personally, consider it a guilty pleasure (and have considered reviewing it many times). Based on a little-known comic, starring minor A-listers, and filmed on a pretty big fucking budget of $75 million (of which it would make only half that at the box office), Virus was a sci-fi horror film with neat effects and decent visuals, underdone by a rather dumb concept and reversion back to genre clichés. A big budget film that likely helped to kill all enthusiasm the major studios had for sci-fi, horror, and risk-taking.

Other than the downfall of creative and inventive vision and the rise of studio skullfuckery, three trends also became apparent during the mid-to-late 1990s. The main one was the increasing use and reliance on CGI, which soon began to replace legitimate artistic and creative talent, wholesale. Special effects via CGI would end up leading to what we now have in the industry: the preference for crappy fake effects over any original vision.

The second was the bipolarity and increase in the shittiness of horror films. Before The Blair Witch Project would come along and officially spell death to the genre by ruining everyone’s time with handheld-shit, there were really two types of horror films that dominated the American cinematic landscape: the slasher, having been reborn thanks to Wes Craven’s shortsightedness; and the monster film. Yes, folks, it’s Scream versus Phantoms, I Know What You Did Last Summer versus Deep Rising, Final Destination versus Lake Placid, Urban Legend versus Virus (and the latter wins every time).

Above: creature concept art for Deep Rising (1998) by the great Rob Bottin.

Deep Rising is a non-stop fun film. Stephen Sommers’ best film (yes, he actually made one of those), Deep Rising is a monster movie that takes its cues from everybody and still ends up being fun. If you haven’t seen it, proudly kick yourself in the genital region and go watch it.

Sci-fi was also at a low point in the late 1990s. Don’t get me wrong, I like a lot of crap from this period, but let’s face it, the number of lasting or game-changing high-quality science fiction (and horror) films from this period were few and far between. Gattaca, Dark City and The Matrix were three major examples, but in hindsight, even they didn’t have that much of a lasting impact on Hollywood’s films. The rest of the genre were either derivative fun flicks, like Deep Rising, or films that attempted to exhibit creativity, but often unraveled due to genre trappings, like Event Horizon and Virus.

Above: Dark City (1998).

While the ending might leave one desiring something more, Dark City is one of the late-1990s’ must see sci-fi films.

Above: still from the sci-fi horror Event Horizon (1997).

Another underrated film with a wonderful concept, great visuals, and violence that was undone by studio interference. Paramount ordered Paul W.S. Anderson (yes, another shitty director who made a decent film) to excise thirty minutes from the film. The footage is now apparently lost.

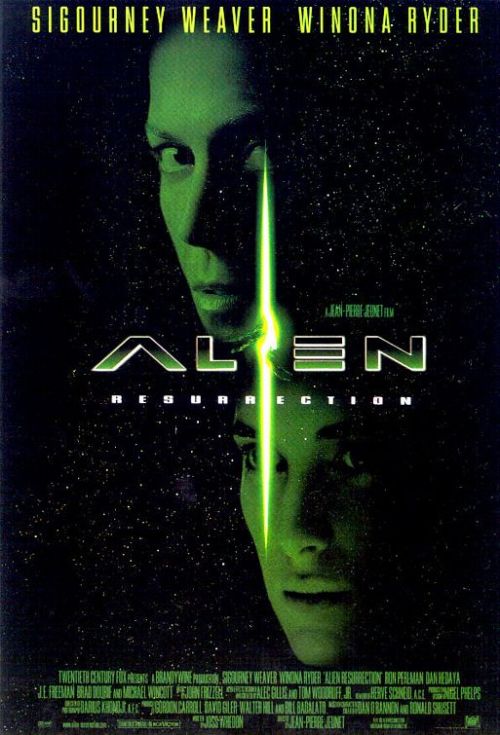

So we finally come to the final film in the original quadrilogy: Alien: Resurrection. It would be directed by renowned Jean-Pierre Jeunet. With a decent cast and a creative team at the helm, what could go wrong?

Alien: Resurrection was a schizoid film, and it’s easy to see how it became a hostage of the late-1990s period of sci-fi and horror. It was clearly a monster film, but it had the sensibilities, and often the self-awareness, of the slasher-lite. Unlike Alien 3, which was fucked before it even got started, A:R actually had the potential to be a classic, just like its fellow Event Horizon.

First of all, A:R pretty much combines a shitload of elements from the preceding films in the series, adds in some bizarre and unused shit from the Alien 3 scripts, and in the end manages to accomplish nothing new. Well, actually, it was better than Alien 3, so I guess that’s a positive start. Right?

You have mercenaries who come aboard a military-science research vessel, where they’re carrying out experiments on human beings with aliens. There’s ship mayhem, alien goodness, clones, human-alien hybrids, a character that turns out to be an android, chestbursters, prison-like settings, and military incompetence. What more could have been recycled? Add in Brad Dourif for some token weirdness, some dark humor, and that French touch, and you have Alien: Resurrection.

Above: some of the cast of Alien: Resurrection.

Left-to-right: Gary Dourdan, Sigourney Weaver, Ron Perlman, Winona Ryder, Kim Flowers.

Above: another shot of some of the cast.

Left-to-right: Winona Ryder, Raymond Cruz, Kim Flowers, Ron Perlman, Sigourney Weaver, Leland Orser.

To write it, they managed to get one only guy this time. Who, you ask? Some no-name guy by the name of Joss Whedon. You know, the guy who directed and wrote the overrated Avengers, I mean, The Bestest Movie EVAR, ZOMG! ORGASM? At that point in time, he’d done Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Toy Story and uncredited rewrites for Speed and… Waterworld?

Above: still of Nathan Fillion and Adam Baldwin in Serenity (2005). That’s one big fucking gun.

Whedon would also be responsible for Firefly, a space western TV series, that eventually led to one of the few legitimately great sci-fi films of the 21st century, Serenity.

So they’ve got one competent writer, rather than half a dozen. But wouldn’t you know it, they got him to do countless rewrites. For instance, Whedon initially wrote an ending with a final battle for Earth, itself… Five versions of it… And none of it ended up in the film. Whedon had to comply with the producers’ demands and make constant rewrites. Like when Hill and Giler wanted a clone of Ripley, Whedon had to change a previous script, which was about a clone of Newt (from Aliens). And, in the end, believe it or not, he was unsatisfied with the way his screenplay ended up on film. According to Whedon, they didn’t fuck it up by making it radically different; they fucked it up simply by fucking it up. It’s almost like the Frenchie director didn’t understand English or something.

But who to direct the masterpiece? Danny Boyle? Not interested. Peter Jackson? Making an Alien film didn’t really excite him. Eventually they brought on Jean-Pierre Jeunet to direct the film, and it shows in some scenes, it really does. A:R often looks visually-stylish, with that trademark Jeunet touch. Having previously done classics such as Delicatessen and The City of Lost Children, and just having finished the script for Amelie, Jeunet was initially surprised that he was offered the chance to direct A:R. He also thought it was a bad idea.

Above: Jeunet (and his pal Caro) would be responsible for one of the most visually-appealing movies of the 1990s, The City of Lost Children (1995).

And he spoke no English… Wait, what? I was just making a joke. He literally spoke no English and had to have a translator. It wasn’t the first, or last, time that a foreign-born director would get fucked over Stateside. Most of them probably actually realized that they’d be getting fucked over though. He had to have a translator, people. The film is fucked!

Jeunet decided that if he was going to get fucked, he might as well bring along his whole crew for the unpleasant ride: for special effects supervisor, Pitof, for cinematographer Darius Khondji, both from The City of Lost Children (Khondji’d also done Seven, among other things, and would later go onto bigger and better projects; Pitof would go onto do Catwoman). He also brought along his pal Marc Caro to do some concept art. According to Wikipedia, Jeunet and his buddies all watched “the latest science fiction” films for references… So basically they weren’t even trapped as a natural result of the time they were in, they basically set themselves up for it.

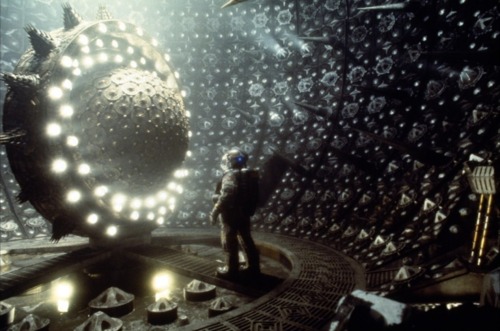

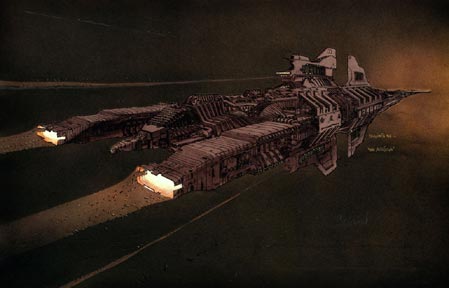

Above: despite moving more towards CGI (hiring Blue Sky Studios for some shots of the aliens), Jeunet wanted all spaceships to be miniatures. Featured here are the Betty and the docking bay of the USM Auriga, by model maker Scott Schneider.

Are Alien 3 and Alien: Resurrection bad films? I’m not here to judge that. Okay, I guess I am. What I am here to judge is how the backdrop of Hollywood at this time fostered hectic productions, clusterfucks, even, with the norm being hiring and firing multiple writers, directors and creative talent. Alien: Resurrection fared better in this department though rampant studio interference still occurred, especially in regards to Whedon’s script. The unfortunate reality of sci-fi and horror at the time meant that Alien: Resurrection’s problems may have had more to do with studio attitudes towards those genres and audiences’ tastes. Neither Alien 3 nor Alien: Resurrection would be the one to dramatically change the landscape of Hollywood.

Man, I’m even more convinced now that if Ridley Scott had to work on Alien 3 or Alien: Resurrection, they still would have turned out to be crap, because he’s not the be-all and end-all, and he certainly wasn’t on Alien. I’m not saying he did a bad job with the first film. He did an amazing job, but he also had the collective creativeness of a whole production team to help him along. If Fincher and Jeunet (and Caro) got fucked over for the ‘90s iterations, I’m sure Scott would have been, too (considering, also, that Scott’s ‘90s period was pretty much shit).

And that’s it. What about the crossovers, you ask? Do I even have to explain those? The 2000s were shit. Okay? Pure shit, with some kernels (of gold) leftover. Adaptations of popular works (and, even then, studios still manage to find a way to fuck those up), sequels, remakes, reboots, reimaginings, readaptations, etc. are/were the norm. Superhero movies seem endlessly popular (and with The Avengers’ success and The Dark Knight Rises pending, this trend doesn’t look like it’ll go away soon). Major studios do not seem to want to finance risky projects, and sci-fi that take chances are few and far between from the majors. They instead relegate these projects to independents, and often distribute them for themselves. From the mid-2000s onwards, there seemed to be very few challenging sci-fi being released: Children of Men, Sunshine, Pandorum, Moon and District 9, as examples.

Above: Inception (2010).

An example of the rare major studio-backed science fiction pic that manages to impress, even if it’s only a mild impression.

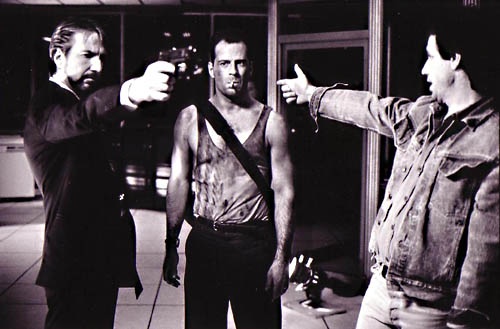

How’ll Prometheus fare? We’ll soon see. If it’s any indication, any science fiction and horror pic has the potential to be good. Hell, I guess anything has the potential to be good. But Alien and Aliens had the good fortune of being created when the times were right. Alien 3 and Alien: Resurrection did not have that luxury. The quality of a film has as much to do with the creative force behind it, but also timing, and that’s something most people often forget. Films are wholly of their time, and they’re often trapped, for better or worse, by the trends and tastes of their respective times. It isn’t a surprise that, say, Die Hard hit theaters when the Reagan era looked to be ending.

Above: Alan Rickman, Bruce Willis and John McTiernan on the set of Die Hard.

One of these days I’m really going to write a paper, like I’ve been meaning to do for years, about Die Hard and Reaganism and its embodiment of the 1980s and the series’ progression as a parallel to the sociopolitical climate. It’ll be even better than this shit…

Akin to that notion is the idea that, say, Aliens found itself in a far more creative atmosphere; studios may have felt that uncreative films would fail to attract audiences, especially with the amount of competition in the 1980s. Alien: Resurrection, on the other hand, found itself in an era with stringent studio control, lack of real imagination, producers who were hesitant on funding risky projects, and audiences whose tastes just sucked.

Good fucking god. I should have just wrote a god damn book. Honestly, this could have been way longer, like book-length. I only really just touched on some of the production aspects for each film and on the history and I skimped over the 2000s. I could have been a lot more comprehensive and/or specific. But then, I probably would have stopped writing soon or later and you’d probably have stopped reading it. If you want to read more on each film’s production, there is a lot of information out there, from books to documentaries to websites (for instance, this Empire feature of Fincher’s Alien 3 experiences).

It’s funny how I’ll forgo writing an actual review to write pages upon pages of this shit. I just wanted the pictures. Enough sidetracking though. I need to write an actual review soon. Maybe I’ll review Virus (1999).

“The Dutch customs once thought my pictures were photos. Where on earth did they think I could have photographed my subjects? In Hell, perhaps?” – H.R. Giger

About this entry

You’re currently reading “The ALIEN Series – Modern Hollywood’s Rise and Fall and Wondering Why the Fuck Ridley Scott Gets So Much Credit for ALIEN,” an entry on Night Train to ¡Mundo Terrible!

- Published:

- June 7, 2012 / 3:51 pm

- Category:

- film history, film series, movie, movies, opinion, review, reviews

- Tags:

- 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, action, alien, Alien 3, Alien Resurrection, Alien series, aliens, Arnold Schwarzenegger, blockbuster, Chris Foss, cyberpunk, Dan O'Bannon, David Fincher, David Giler, David Twohy, Die Hard, Eric Red, film analysis, film series, Gale Anne Hurd, Giger, H.R. Giger, history, Hollywood, horror, James Cameron, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, John Carpenter, Joss Whedon, Michael Cimino, Movies, New Hollywood, Paul Verhoeven, Predator, Prometheus, Ridley Scott, Roger Corman, Ron Cobb, Ronald Shusett, sci-fi, science fiction, Star Wars, Syd Mead, Vincent Ward, Walter Hill, William Gibson, xenomorph

28 Comments

Jump to comment form | comment rss [?] | trackback uri [?]